In Studio With: Dave Strachan, Strachan Group Architects

For more than three decades, Dave Strachan has been a defining voice in New Zealand architecture — a practitioner whose work bridges craft and construction, environmental responsibility and human experience. As founder of Strachan Group Architects (SGA), he leads a practice known for its rigorous passive design principles, hands-on ethos, and deep respect for climate, context, and materiality. “Buildings are for people,” Strachan says, a simple but enduring idea that sits at the heart of his philosophy.

His background as a builder, educator and designer weaves through SGA’s work, grounding each project in practicality while elevating it through thoughtful detail and an unwavering commitment to sustainability. Whether mentoring young architects, exploring new timber technologies, or testing ideas in the studio workshop, Strachan approaches architecture as both craft and responsibility — an ongoing pursuit of spaces that “uplift the human spirit.”

In this conversation, he reflects on the principles that have shaped his career, what has evolved, and why good design — honest, responsive, and well-made — still matters.

What are the three most important ideas, strategies, or approaches that define your design philosophy?

Our key mantra at SGA is “To craft environment-friendly buildings of place that uplift the human spirit” so fundamentally buildings are for people and that has not changed over the years. We often frame it as “form follows climate, context and landform” which links into making sure we deliver good passive design on each particular site. Other key principles are to deliver practical construction solutions that respect clients’ budgets

Of these, what has changed over the course of your practice, and what has remained constant?

Probably not much other than hopefully getting better at what we do based on a long period of experience in the industry. One change has been the addition of a strong focus on teaching both within the practice and since the early 2000’s at Unitec and UofA schools of architecture. That is an investment in the future as we can guide young architecture students in the early stages of their careers. Often in jest I call it “polluting young minds” !

You began your career as a builder before moving into architecture. How has that hands-on background shaped the way you design?

There is no doubt that having been a builder before architecture school is embedded in my psyche. The challenge for me at Uni was to combine the benefits of good design with practical construction methods.

Does that builder's instinct still surface when you're detailing or on site – particularly in understanding how builders and contractors view the construction process?

Yes definitely and it leads to a collaborative environment rather than a combative relationship, where we respect each other’s perspectives on a project and work together for a great result.

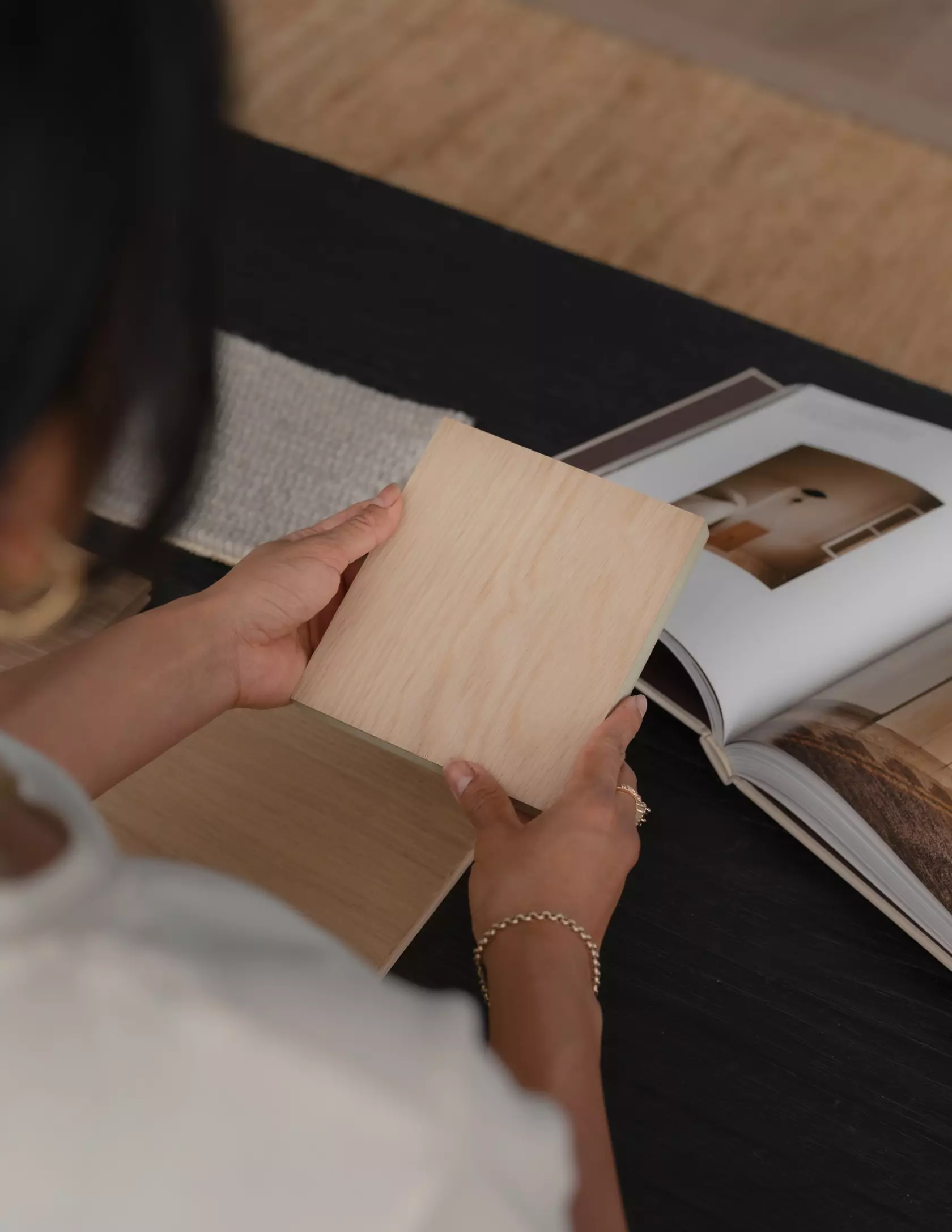

Timber features strongly in your work. What draws you to it as both a designer and a maker?

Timber has many attributes, from smell, texture, grain, being relatively light-weight and varied in colour, right through to being good at absorbing CO2. People react well to spaces that feature timber I think because it is a natural product with unique characteristics, as opposed to say a bland painted wall.

Timber construction technology is also evolving rapidly – from hybrid fabrication to treatments that enhance performance. How do these advancements change your approach, do they change what’s possible in terms of form, finish, or long-term performance?

We have worked with many types of prefabrication systems since the early 2000’s (volumetric, panel, component, module, hybrid etc) including CLT (cross laminated timber) SIP panels (structural insulated panels), and have developed interfaces from our CAD program into CNC (computer numerically controlled ) fabrication. The key seems to be in selecting what is appropriate for the project, client brief and budget together with ensuring good environmental performance in terms of durability, embodied energy and future operating energy.

SGA is recognised as being one of our industry leaders in Environmentally Sustainable Design - an early adopter, if you will. With technology now offering architects powerful new tools for analysis, modelling, and material exploration, and as suppliers increasingly champion environmentally conscious products, how has this shifted your approach to designing and specifying materials?

The tools still have some way to go to be user friendly and nimble for design and certification purposes so with good passive design and appropriate material choices (avoid red list materials with high harmful chemical content and toxicity) you are already most of the way there.

There's often a gap between sustainability as a code requirement or marketing term, and sustainability as a core value. How do you navigate that – especially when balancing environmental principles with client priorities like cost and aesthetics?

In many ways the code, being a largely prescriptive document stifles innovation and leaves out some of the key principles of sustainability. A simple example is there is no requirement to provide shading of large areas of glazing and maybe because of this (now with the increased insulation standards) many buildings are now experiencing overheating. Some clients are savvy and want their building to perform well and we question clients’ beliefs early, but for those who seem less interested we embody the core passive design principles in their project anyway, with perhaps less active systems than others (like solar) We also have a 12 point sustainability matrix that we use and try to activate as many of those principles as we can in each project.

How do you define craftsmanship in the context of contemporary architecture, especially when working with advanced manufacturing or engineered materials?

We definitely try to embrace the new construction techniques and materials otherwise you end up stuck in the mud!

What opportunities for craft exist when new technology intersects with traditional tools of design and construction?

Having our 3 sons working in construction and design means we get a younger more current perspective how they are building things as they are more build specific. This can then feed into our approach to designing buildings, but there is no substitute for seeing craft that you can feel, touch or smell and the feeling that someone took a lot of care in creating that part of a building. We are still humans, not machines, even though machines have many benefits of course.

If you could change one thing about how architecture is practiced or perceived in Aotearoa, what would it be?

There are a plethora of TV home shows featuring disaster projects, budget blow-outs, and showing buildings with highly unattainable budgets for most New Zealanders, and the 10 minute do-up wonders. I would love to be able to show New Zealanders the benefits of good design, and the impact that can have on people’s lives and well-being. Perception of the supposedly high architect fees mean many clients opt for poor design outcomes that are poor environmentally, longevity-wise and don’t uplift the spirit of those who inhabit them. Even early input from a good architect can add so much value to a project which is supposed to last at least 50 years, surely that is worth something?

Are there architects – past, present, local, or international – who exemplify this approach?

Without naming any names in case I miss anyone out, there are quite a number of young NZ architects who are doing great work often with modest budgets and an inventive way of using standard materials, so a call out to them. For me Group Architects embodied that early hands-on, self-build NZ pioneer spirit and went searching for a New Zealand-ness as opposed to being driven by European models.

What do you hope people feel when they inhabit one of your buildings?

We talked about uplifting the human spirit, the smile on their faces, the way the light comes into the spaces, that’s gold.

And when you return to a completed project and see how clients have made it their own, does anything about how they use the space surprise you?

I always figure when a building is complete it’s great seeing clients “making it their own”, so how they occupy the spaces with their furniture and personal items means they have taken real ownership, not some picture-perfect environment where you wonder does anyone actually live here…

Finally, on a slightly different note… can you tell us a bit about your band?!

We have 3 architects in the band, Cam Pollock on bass from DKO, Gary Lawson from Stevens/Lawson on drums, me on lead guitar and our singer/guitarist/writer Dan Wrightson, the non-architect, decided to use a common building term the “door jamb”, with the “s” added as we do a few original songs but mostly covers hence the jamming reference. Our daughter says we play all the “bangers” often at the Horse and Trap in Mt Eden and the Mangawhai Heads club…